A Brief History of Commerce, Service and Industry in the Littleton Area

Littleton’s economic good fortune may be traced to rivers and roads.

In the 1760s, after the defeat of France by the British in the “French and Indian War”, the area’s first white settlers could safely make their way up the Connecticut River to unpopulated townships created by the British monarchy and granted by New Hampshire Governor Benning Wentworth. Among these townships was Littleton, originally and variously known as Chiswick and Apthorp.

In the 1760s, after the defeat of France by the British in the “French and Indian War”, the area’s first white settlers could safely make their way up the Connecticut River to unpopulated townships created by the British monarchy and granted by New Hampshire Governor Benning Wentworth. Among these townships was Littleton, originally and variously known as Chiswick and Apthorp.

The location offered many advantages: two river valleys, the Connecticut and the Ammonoosuc, both with generous acres of fertile land. The Connecticut River was broad and unnavigable where it coursed past Littleton. It was a torrent that plummeted approximately 360 feet through several townships and became known as Fifteen-Mile Falls. The Ammonoosuc River, with its drop of 235 feet within the town’s limits, was soon favored. A fellow named Little built a mill, and the commerce of the region was launched.

The Ammonoosuc’s head simultaneously fueled as many as ten mills in the 19th century. These engines of commerce first processed wood and grains, then tanneries and factories that produced finished goods. Littleton attracted a skilled labor force of men and women who stitched shoes, gloves and harnesses. The ease of access to markets via the Connecticut River complemented the natural assets, and the town became preeminent in enterprise.

The arrival of railroads changed almost every aspect of commerce in New Hampshire. The iron horse came north (up the Merrimack River) from Concord to Plymouth, then veered northwest, up the Baker River Valley to the town of Woodsville, NH on the Connecticut River. From this terminus (and junction with rails that ran west and north) the tracks crept east, along the Ammonoosuc to Littleton.

[It may seem peculiar to today’s Interstate 93 highway travelers, but there was no useful north-south thoroughfare in northern New Hampshire until the 1920s. A crude carriage path was cut along the Pemigewasset Valley and through the Notch in 1820s. There was never a railroad through Franconia Notch.]

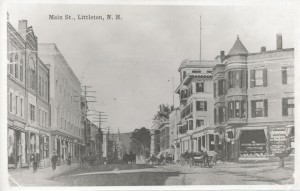

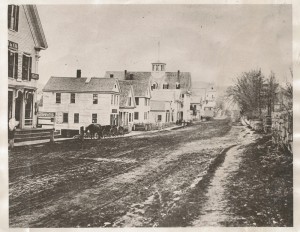

Along the Ammonoosuc, bustling towns needed banks and lawyers and hotels (for rail passengers). The pace of development was breathtaking and, when the tracks reached Littleton in 1853, the trains progressed no further. The Civil War, political feuds and a host of lawsuits delayed further development. Littleton was the rail terminus of the region for almost 20 years. This prosperous interval yielded the beautiful Main Street and downtown of Littleton. Bricks, timber, tourists, dry goods, and fresh oysters traveled from all points in New England and Canada to Littleton’s rail station where products found their way to local stores and to shippers who supplied the region.

The region’s heritage of tourism is discussed here. Until the 1880s, when the railroads extended beyond Littleton to Portland, Maine and Montreal, Canada, constituent enterprises arose amid the prosperity of the Industrial Revolution. Most notably, in Littleton was the stereoscopic industry. The Kilburn brothers, native Littleton photographers, found vast markets for their cards displaying mountain scenery, and, later, exotic locales and humorous tableaus.

Well into the 20th century, despite the Great Depression, Littleton remained the “Crossroads of Northern New England”. The leather and stitching industries lagged and failed. The wood products industries moved away. The diminishing tax base meant that public services and maintenance frayed. But Littleton’s fundamental strengths, a skilled labor force, its importance as a transportation hub and the potential of its rivers endured.

In the 1950s, the Samuel C. Moore Power Station harnessed the Connecticut River’s Fifteen-Mile Falls. The hydroelectric station produces in excess of 200 million kilowatt hours of electricity annually. Its construction employed hundreds of local folks and required the flooding of two neighborhoods: Vermont’s Upper Waterford and Littleton’s Pattenville. The Moore Station endowed the municipality with inexpensive electricity, both domestic and industrial, and was an enormous boost to the property tax base. It also introduced to the Littleton area a wave of white-collar professionals such as engineers, large-scale contractors and trained administrators.

The completion of the federal Interstate highway system in the 1980s assured that Littleton would remain the crossroads of northern New England, for trade, manufacturing and enterprise.

A Brief History of Hospitality, Recreation and Culture in the Littleton Area

Littleton is located in a region renowned for its natural splendor, scenic variety and rich history.

The White Mountains have been a celebrated destination since the early 19th century, when artists, writers and poets discovered the rugged landscape. They sought to shape a culture for a new nation. The mountains and forests embodied the glories and perils that confronted the world’s first experiment in human freedom. Here began the new aesthetic that turned its back on the elitism and despotism of the Old World.

Accounts of the region by Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson caught the imagination of readers. Famed artists of the “Hudson River School” portrayed the mountains as forbidding, yet magnetic in their rustic allure. The works of Thomas Cole, Asher Brown Durand, Thomas Hill,Frederick Church and a dozen other painters were reproduced and sold by the thousands….

All this fuss was great advertising for a region that was not ideal for farming and too remote from markets for large-scale manufacturing. Enterprising settlers converted their rustic homes to taverns and inns. Hospitality has been a tradition since before the Civil War.

As America’s 19th century progressed, the nation yielded a prosperous middle class as the result of the Industrial Revolution. Simultaneous with the creation of this “leisured” generation of moneyed folks – families who sought to escape the soot and heat of the cities – the railroads reached into the mountains of northern new England.

Since the 1850s, Littleton has been the hub for travelers to the White Mountains. It is located on the “Western Slope” which extends from Mount Washington (at 6,288 ft / 1917 km, the highest peak in the northeastern United States) westward to the Vermont border. For nearly 30 years, Littleton was the terminus of rail travel to the mountains. Thayers Hotel, constructed in 1850, was among the first “railroad hotels” built specifically for the new class of travelers. The old inns that served drovers and teamsters were soon supplanted by these modern hostelries.

As the 20th century began, Grand Hotels dotted the region. These were huge white palaces, ringed by broad verandas that overlooked golf courses framed by the glorious mountain ranges. Each hotel had a coach that shuttled passengers to and from Littleton. The hotels were supplied by Littleton merchants and staffed by Littleton workers. A heritage of hospitality and recreation was ingrained within the town’s identity.

At the turn of the century, three developments shook the placid routines of the Gilded Era. The motor car made its appearance around 1905, and within a couple of decades, brought the Littleton area within the reach of yet another class of traveler. Accommodations were more modest – cabins and tents catered to the new breed and their horseless carriages. Small theme parks sprouted as roadside attractions – and several survive to delight the gang in the back seat. Besides serving the lodging and dining needs of the motorists, Littleton became a locus of service and sales for all matters automotive.

The second development was a fervent movement to protect the region’s vast verdant landscape. It was sparked by wide-scale destruction of the forests by “Timber Barons” and their careless harvesting practices that led to ceaseless forest fires. The logging industry had thrived with the arrival of the railroad. But the public was enraged by the recklessness and greed that scarred the hillsides and darkened the the sky with ashes. U.S. Senator John W. Weeks, a summer resident of the area, promoted an ambitious effort to save the precious wildlands. The White Mountains National Forest was established by federal law in 1918. Today, the WMNF comprises 1,225 square miles which are laced with hiking trails (including the famed Appalachian Trail,) yet continue to support a supervised and responsible wood products industry.

The federal measures were matched by the state’s development of an extensive park system. The outdoors was more than greenery. It was a place to participate in novel modes of recreation.

Here was the third occurrence that shaped the 20th century: the rising popularity of wilderness adventure. Hiking and camping became popular. Hiking clubs cut and maintained trails. State parks offered campsites. Littleton provisioned these enthusiasts with food and gear. The town is still a necessary stop for visitors who venture into the woods or scale the daunting peaks.

The Littleton area continued to attract artists, poets and musicians, especially as summer residents. George Gershwin and Jascha Heifetz visited Samuel Chotzinoff, NBC opera producer and prolific composer, at his summer home in Littleton. Author Ernest Poole, the first winner of the Pulitzer Prize (1918), lived in nearby Sugar Hill, and was neighbor to poet Robert Frost. Both frequented Littleton’s merchants, barbers and banks.

In a class by herself was Eleanor Hodgman Porter (1868-1920), the Littleton native who penned the immortal Pollyanna, a best-seller when it appeared in 1913. In 2002, a statue of Porter’s fictional creation was erected on the library lawn where Pollyanna’s outspread arms beckon all to “Be Glad!”

Until the 1940s, hospitality and recreation were summer affairs, and Littleton’s winters were chilly and low-key. By mid-century, a new crop of visitors animated the snowy months: skiing enthusiasts. The sport was boosted when the state completed the Cannon Mountain Aerial Tramway in 1938. College-age men and women arrived on “Snow Trains” and donned “hickory wings” to speed down the serpentine slopes, but, within a decade, skiing was a genuine industry that catered to entire families. Winter visitors needed lodging and dining. The season was no longer a dormant interlude but a lively whirl of races, parties and whizzing chair lifts.

Throughout changing times, Littleton has genially hosted and promoted the enterprises that gratified adventurers and tourists.

The Littleton area, with its storied villages, lofty hills and hushed forests, is unequaled in its hospitality. It embraces the seekers of every epoch of adventure. It inspires artists, writers and photographers. It delights young families with its array of cheery diversions. It challenges the daring. It casts a romantic spell over lovers of every age. It offers the plushest accommodations one may seek, or the most rustic.

It has been written that this place is “how the good life used to be”. Around here, they say it’s just the way it has always been, and always should be. To learn more about the rich history of the Littleton Area, please visit the Littleton Historical Society webpage, or come on in to visit the Historical Museum in the Littleton Opera House on Wednesdays from 10 am to 2 pm or by appointment.

Take the Littleton Historic Walking Tour!

Main Street owes its appeal to topology, economics and civic pride. On a ridge north of the Ammonoosuc River, 60 feet above the riverfront mills, Main Street’s commercial district arose along an 1820 coach road.

Download the Historic Littleton Walking Tour Brochure [731 KB pdf]